GYDA VALTYSDOTTIR – EPICYCLE II

You’re forgiven if you do not immediately recognize her name, especially if you’re not from Iceland. But it is time to change that now. Gyða Valtýsdóttir is a founding member of the band Múm. She is a classically trained artist, with a lot of experience in music for films, installations, dance – among other settings. Epicycle II is her third album, after award-winning Epicycle I (2017) and Evolution (2018), which was the first album presenting her own compositions.

Epicycle is “a constellation of written music spanning from ancient to avant-garde”.

Epicycle I focused on the ‘ancient’, on Epicycle II Valtysdottir presents compositions by some of Iceland’s prominent contemporary composers: Ólöf Arnalds, Daníel Bjarnason, Jónsi, Anna Thorvaldsdóttir, Skúli Sverrison, Kjartan Sveinsson, Úlfur Hansson and María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir.

Other than on the first part of Epicycle, the compositions for this second edition were specially written for and/or with her (with the exception of Daniel Bjarnason’s Air To Breath, which is the only track that was released before).

The album presents a vast range of (contemporary classical) styles, from ‘almost pop’ (on the vocal tracks Safe To Love and Liquidity) to more avant-garde experiments (such as on Jónsi’s Evol Lamina – read that backward).

Valtisdottir manages to connect all these tracks together into a spectacular album avoiding trodden paths, luring the listener into more complex music with so much self-confidence that it only feels like the natural next step.

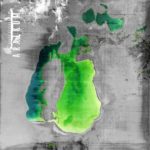

GALYA BISENGALIEVA – ARALKUM

Galya Bisengalieva is a Kazakh/British violinist. But apart from her contemporary classical experience she also has a firm focus on experimental and electronic music: she has worked with giants like Steve Reich, Suzanne Cianni, Laurie Spiegel, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, as well as commissioning and performing works by Hildur Gudnadottir, Sarah Davachi, Ipek Gorgun and Mica Levi. Though her music can be classified as ‘contemporary classical’, that is only part of the story. And then I don’t even mention her contribution to Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool, or to the soundtracks of Suspiria and Under the Skin. How’s that for an introduction?

Aralkum, her first full solo album (apart from 2 earlier EP’s), is filled with a strong environmental message: “the shrinking of the Aral Sea to 10% of its original size, caused by the diversion of the rivers that fed it by Soviet irrigation projects”. It has been called “one of the worst environmental disasters on the planet”. In an attempt to save the lake, Kazakhstan constructed the Kokaral Dam.

This background story explains the somber undertones of the pieces on Aralkum, which is split into three parts: “pre-disaster, calamity, future”.

There may be some hope left for the future, but we have to learn from our mistakes – this much is sure.

Bisengalieva has a very personal way of combining string arrangements with electronics. Both are equally important, supporting each other. But if you come from the more ‘modern classical’ background the album may feel primarily electronic-based – and vice-versa too, perhaps.

She defines her own unique place in the current musical spectrum with an album where all of her previous experiences melt together into an overwhelming listening experience.

LUKAS LAUERMANN – I N

“I N does not start with the first work. The end is at the beginning.”

For Lukas Lauermann, cellist and composer from Vienna, Austria, the music on this album began with listening. And it ends with ús listening to it. Which means another new beginning.

If the first track (Trusion – all track titles can be preceded with “IN”) would be the conclusion, it would probably be the end of a rather tragic story. In the (22) tracks on I N, Lauermann explores many different moods. His classical training clearly shows in his compelling cello sound, but he is not afraid to merge this with surprising music elements that take his compositions ‘out of the box’.

It turns out he is not afraid to merge some surprising elements into the accompanying video, too:

“As the music navigates the 12 semitones of the traditional scale, accompanying sounds beyond the central cello rear their heads: tuning forks, synthesizer, and piano. Sometimes the sounds are altered electronically. Sometimes they are listened to through the cello, which turns the venerable string instrument into a soundboard for external musical sources. [ … ] And best of all: Even if you know all of that… you won’t be able to hear it! You can simply let yourself sink INto it!”

LUKAS LAUERMANN – HERENT FULL